January 11: Hamilton Born, Insulin Saves Lives, and Earhart Crosses the Pacific

January 11 marks three moments when humble origins produced greatness, scientific breakthrough transformed terminal illness into manageable condition, and audacity conquered an ocean. On this day, a Caribbean boy was born who would architect American finance, doctors first administered a hormone that would save millions from diabetes, and an aviator proved that courage and skill could span the Pacific solo. These stories remind us that birthplace doesn't determine destiny, that some discoveries deserve the word "miracle," and that barriers exist to be crossed by those brave enough to try.

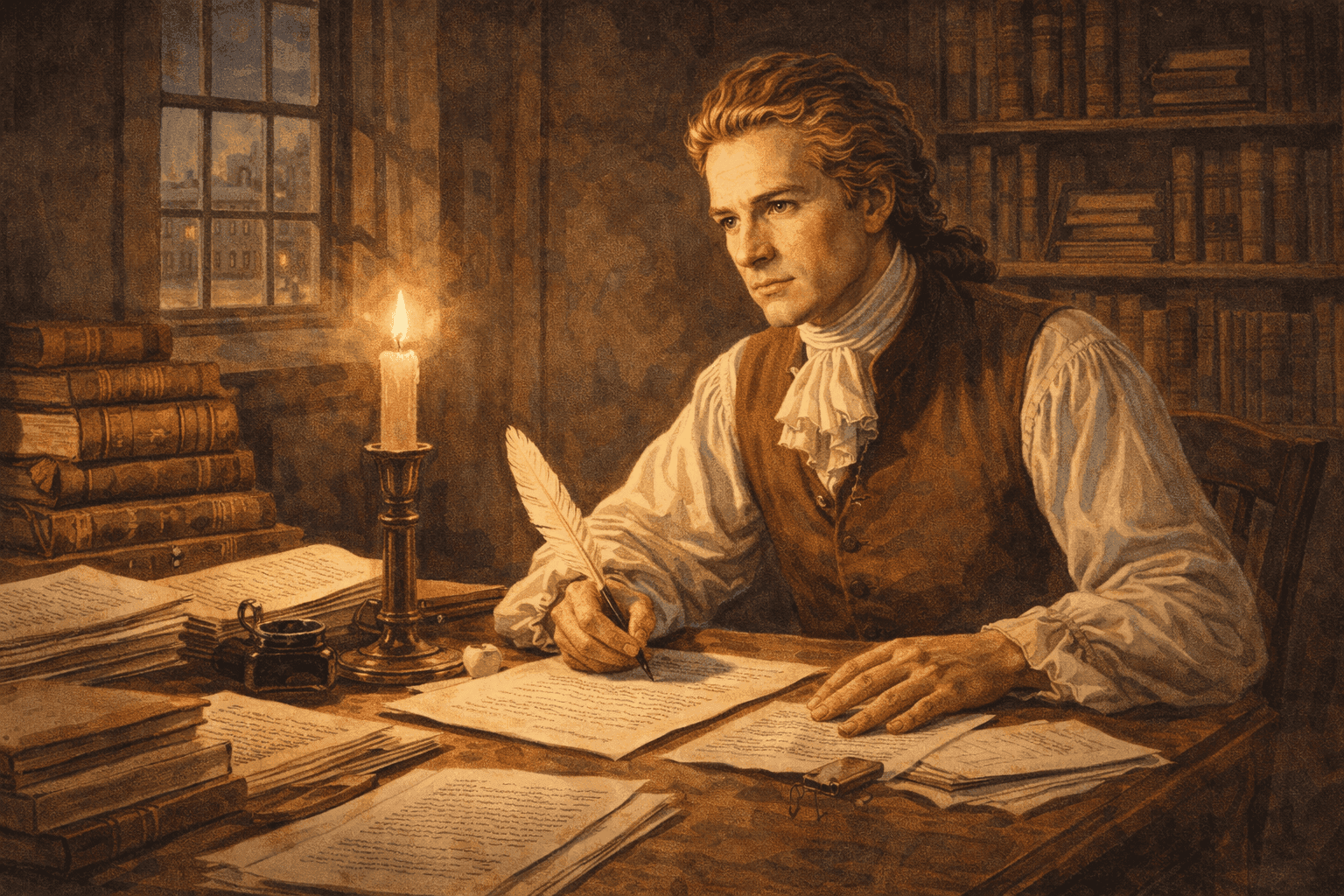

The Bastard Orphan Who Built a Nation

On January 11, 1755 (or 1757—the date is disputed), Alexander Hamilton was born on Nevis, a tiny Caribbean island, to an unmarried Scottish merchant and a French Huguenot woman. His origins were unpromising: born out of wedlock, abandoned by his father, orphaned when his mother died when he was 13, working as a clerk while educating himself voraciously. Yet local merchants, impressed by his brilliance and ambition, pooled funds to send him to New York for education. Hamilton arrived in America in 1772, a teenage immigrant with nothing but talent, determination, and extraordinary intellectual gifts that would reshape a nation.

Hamilton became indispensable to the American founding: Washington's aide-de-camp during the Revolution, co-author of The Federalist Papers arguing for constitutional ratification, and first Secretary of the Treasury who essentially created American capitalism—establishing the national bank, federal assumption of state debts, and systems of credit and taxation that made the United States economically viable. His vision of strong federal government and commercial economy clashed with Jefferson's agrarian republicanism, creating America's first political parties and defining debates that continue today. Yet Hamilton's brilliance came wrapped in fatal flaws: arrogance, extramarital affairs, political enemies he couldn't resist antagonizing. His life ended in 1804 when Aaron Burr shot him in their duel—Hamilton dying at 47, having accomplished more in those years than most do in lifetimes. January 11, 1755, reminds us that greatness emerges from unexpected places, that immigrants often see adopted nations' potential more clearly than natives, and that founding nations requires not just military victory but economic architecture enabling prosperity. Hamilton demonstrated that intellect and ambition could overcome birth's disadvantages, that financial systems matter as much as constitutions in nation-building, and that genius doesn't guarantee wisdom or happiness. The Caribbean orphan who became treasury secretary proved America's revolutionary promise—that talent and determination matter more than pedigree—while his tragic death proved that brilliance can't overcome poor judgment in choosing dueling partners. Hamilton's birthday celebrates not a perfect man but an essential one, whose vision of commercial republic and strong national government ultimately prevailed even as his political opponents defeated him personally.

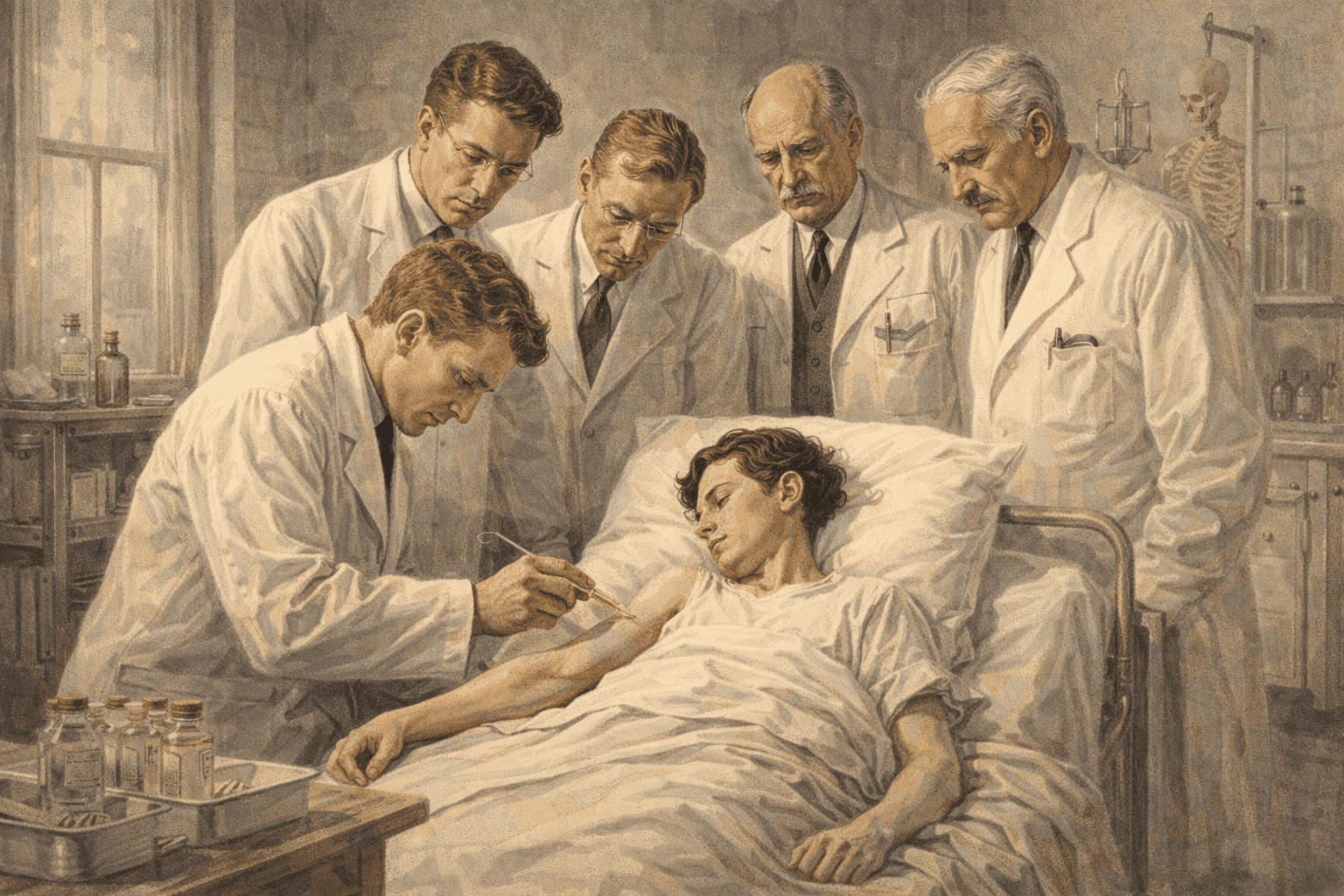

The Miracle in a Syringe

One hundred sixty-seven years after Hamilton's birth, on January 11, 1922, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson became the first person to receive insulin as treatment for diabetes. The boy was dying—weighing just 65 pounds, falling in and out of diabetic coma, days or weeks from death as his body couldn't process sugar without the hormone insulin his pancreas no longer produced. Doctors Frederick Banting and Charles Best had extracted insulin from cattle pancreases, purified it, and tested it on dogs. Thompson's injection represented desperate hope: the extract might kill him, but diabetes certainly would. Within 24 hours, Leonard's blood sugar dropped to near-normal levels. He lived fourteen more years—not cured but managed, transformed from terminal patient to chronic condition.

Insulin's discovery ranks among medicine's greatest breakthroughs. Before 1922, diabetes diagnosis meant slow starvation death—doctors could only prescribe extreme dietary restrictions that delayed but couldn't prevent fatal outcome. Insulin didn't cure diabetes but made it survivable, transforming certain death sentence into manageable condition requiring daily injections but compatible with normal life. Banting and Best could have become extraordinarily wealthy by patenting insulin; instead, they sold the patent to the University of Toronto for one dollar, believing life-saving medicines shouldn't enrich discoverers at patients' expense. Their generosity enabled affordable insulin production, though pharmaceutical companies would later complicate that legacy with expensive proprietary formulations. January 11, 1922, reminds us that some discoveries genuinely deserve the word "miracle," that scientific breakthroughs can literally resurrect dying children, and that researchers' choices about commercialization profoundly affect who benefits from medical advances. Insulin demonstrated that understanding biological mechanisms enables replacing what bodies can't produce, opening an era of hormone therapy that would transform medicine. Leonard Thompson, the dying boy who became first insulin patient, lived to see millions saved by the discovery that rescued him—testament to how one breakthrough can cascade across time, saving not just one life but millions, turning death sentences into manageable conditions, and proving that sometimes science really does work miracles. The syringe that saved Leonard Thompson contained more than insulin—it contained hope that medical understanding could outwit fatal diseases.

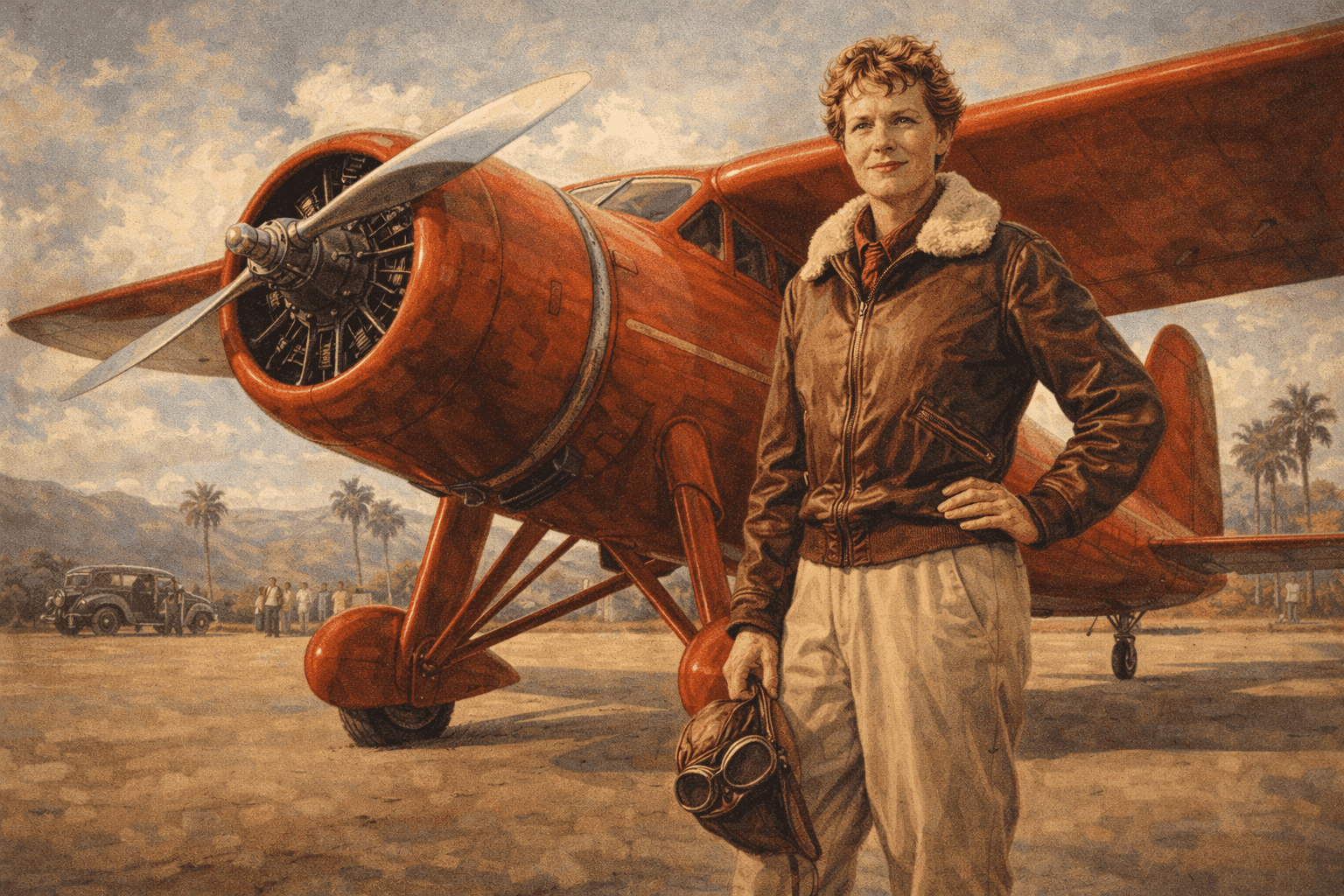

Alone Across the Pacific

Thirteen years after insulin's first use, on January 11, 1935, Amelia Earhart completed the first solo flight from Hawaii to California, landing in Oakland after 18 hours crossing 2,408 miles of open Pacific. The flight was dangerous—no landmarks over ocean, navigation by instruments and dead reckoning, mechanical failure meaning certain death in frigid water. Yet Earhart, already famous for being first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, sought new challenges. She wanted to demonstrate that such flights were practical (airline service between Hawaii and California would begin months later), to prove her own capabilities, and to push aviation's boundaries. The flight succeeded spectacularly, though it would be her second-to-last major aviation achievement.

Earhart's Pacific crossing demonstrated both aviation's rapid advance and her exceptional skill. Twenty years earlier, the Wright Brothers had barely crossed fields; now individual pilots could span oceans. Yet such flights remained extraordinarily dangerous—requiring precise navigation, mechanical reliability, and nerves steady enough to face hours alone over water knowing any mistake meant death. Earhart made it look achievable, inspiring others to attempt what seemed impossible. Two years later, attempting to circumnavigate the globe at the equator, she vanished over the Pacific—disappearance transforming her from accomplished aviator into legend, mystery ensuring immortality her achievements alone might not have guaranteed. January 11, 1935, reminds us that progress requires individuals willing to risk everything for firsts, that breaking barriers often means literally going where no one has gone, and that sometimes the only way to prove something possible is simply doing it. Earhart's Hawaii-California flight wasn't her most famous accomplishment—that distinction belongs to her disappearance—but it demonstrated the calculated risk-taking and technical mastery that defined her career. She flew alone across the Pacific not because she was reckless but because she'd calculated risks, trusted her abilities, and believed aviation's future required proving such flights feasible. The woman who landed in Oakland that January day wouldn't live to see airlines routinely cross the Pacific, but her flight helped make that routine possible, proving that distance and ocean were barriers technology and courage could overcome.