February 20: Binding a Nation, Opening the Gallery, Orbiting the Earth

February 20 marks a day of remarkable reach and ambition in American history. From the establishment of a system that would bind a fledgling nation together, to the opening of doors that would preserve humanity's creative spirit, to a voyage that would transcend Earth itself, these three milestones share a common thread: the drive to connect, to preserve, and to explore. Together, they remind us that progress requires both looking inward at what unites us and reaching outward toward what lies beyond.

The Network That Built America

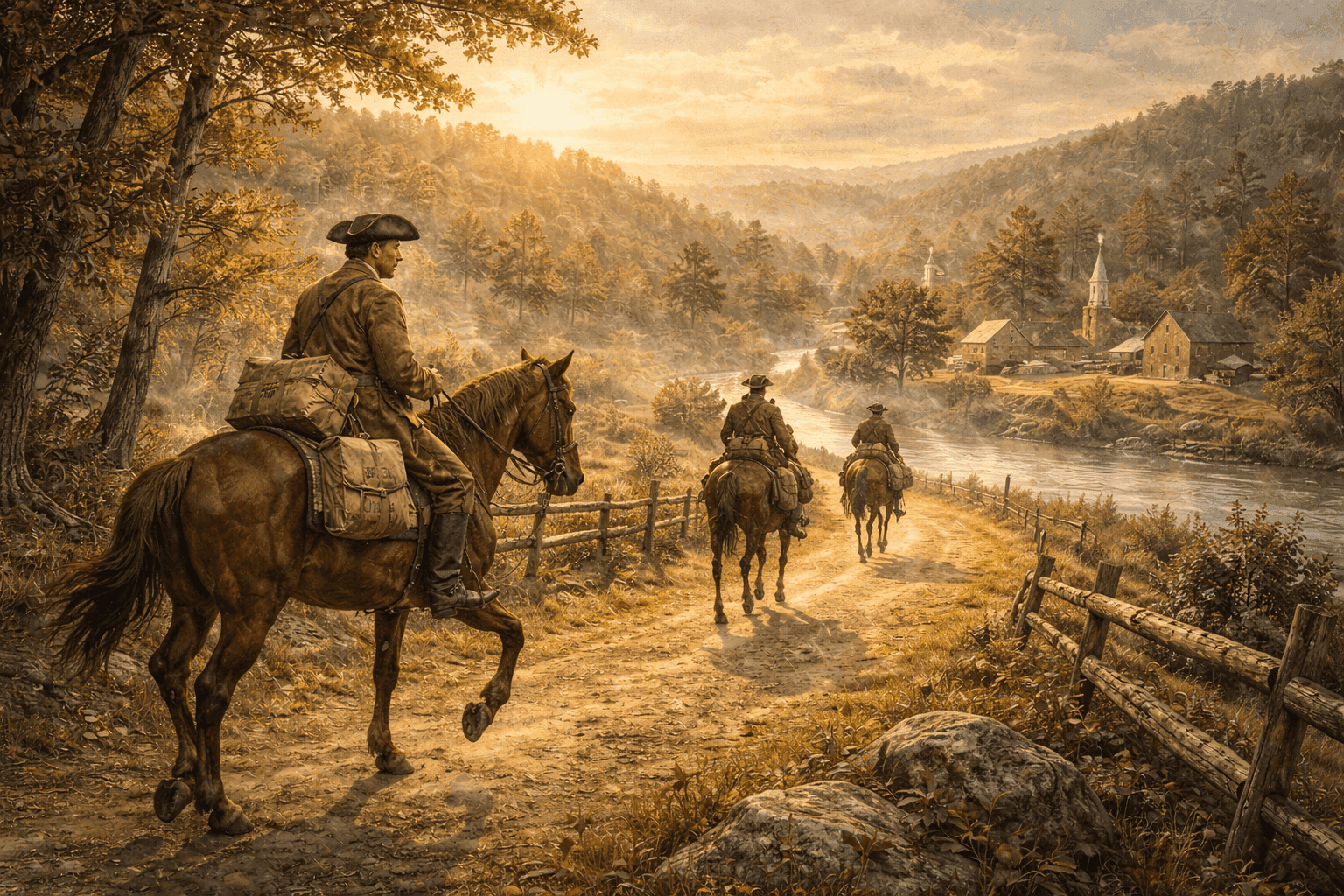

On February 20, 1792, President George Washington signed legislation establishing the United States Post Office, transforming scattered colonial mail routes into a unified national institution. This wasn't merely about delivering letters—it was about creating the connective tissue of democracy itself. The Post Office would carry news between distant communities, enable commerce across vast territories, and ensure that citizens from Georgia to Massachusetts could participate in the grand experiment of self-governance.

The impact was profound and immediate. As post roads multiplied and mail delivery became reliable, newspapers could circulate nationwide, merchants could conduct business across state lines, and families separated by the frontier could maintain bonds. The postal service became one of the young republic's largest employers and most visible symbols of federal authority. What began as a practical necessity evolved into something more fundamental: infrastructure that didn't just move correspondence, but wove together the fabric of a nation still finding its identity.

A Palace for the People

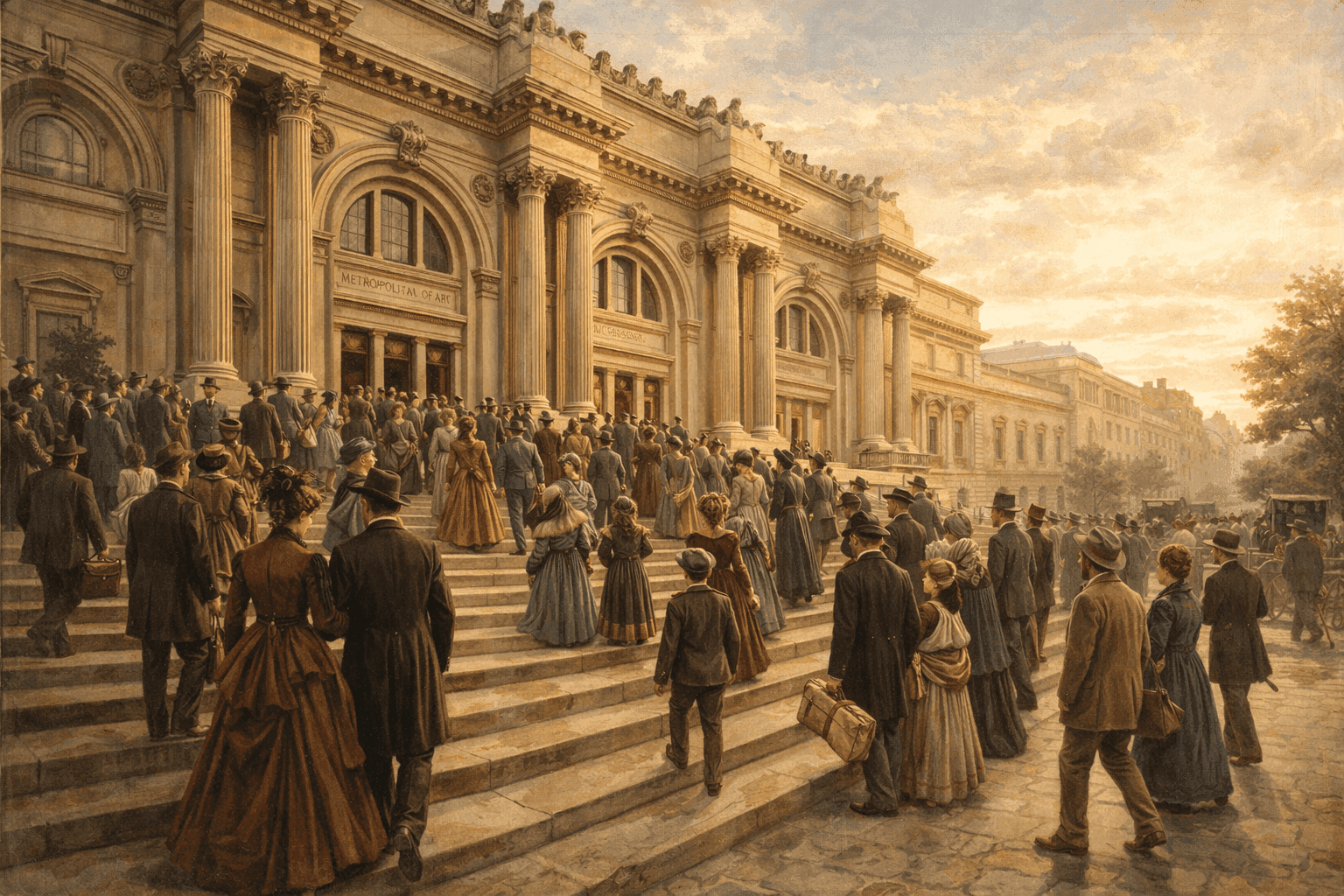

Eighty years later, on February 20, 1872, another kind of connection was forged when the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its doors at 681 Fifth Avenue in New York City. The founders envisioned an institution that would be "located in the City of New York, for the purpose of establishing and maintaining in said city a Museum and Library of Art." What distinguished this vision was its democratic impulse: art shouldn't be the exclusive province of the wealthy, but a shared inheritance accessible to all.

From its modest beginning—a Roman sarcophagus and 174 mostly European paintings displayed in a rented building—the Met has grown into one of the world's encyclopedic museums. Today it houses over two million works spanning five millennia and six continents, from Egyptian temples to contemporary installations. The museum's journey mirrors America's own evolution: from a young nation looking to Europe for cultural validation to a global crossroads celebrating human creativity in all its forms. The Met fulfilled its founders' radical proposition that beauty and knowledge belong not to dynasties or elites, but to everyone willing to walk through its doors.

Three Times Around the World

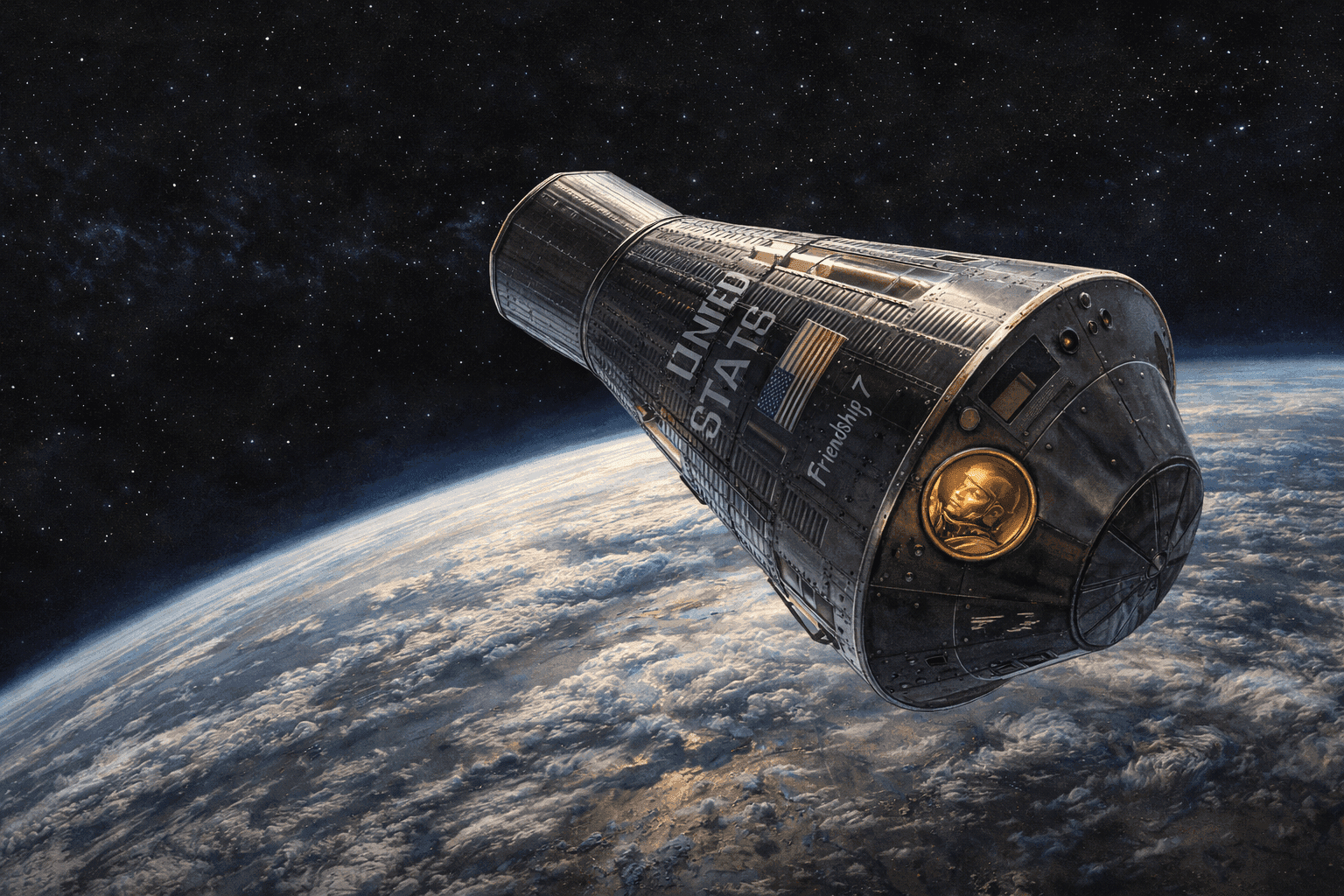

On February 20, 1962—ninety years to the day after the Met's opening—astronaut John Glenn climbed into the cramped Friendship 7 capsule and prepared to push human reach beyond anything previously imagined. His mission: to become the first American to orbit Earth, circling the planet three times at 17,500 miles per hour while the nation held its breath. As Glenn lifted off from Cape Canaveral, he carried not just scientific instruments, but the hopes of a country locked in a Cold War struggle to prove that democracy could match communism's technological achievements.

The flight nearly ended in disaster when telemetry suggested Glenn's heat shield might be loose—a malfunction that could incinerate him during reentry. Mission Control kept the news from Glenn for much of the flight, though the former Marine Corps pilot maintained his characteristic calm throughout. When Friendship 7 splashed down in the Atlantic after four hours and 55 minutes, Glenn emerged not just as a hero but as proof that American ingenuity and courage could prevail in the space race. His journey expanded the boundaries of human possibility, showing that if we could bind a nation with letters and preserve culture in museums, we could also reach for the stars themselves.